Today was another one of those “days of days” when President Trump announced retaliatory tariffs against India and, for some reason, Japan. At the same time, he threatened the European Union again and boasted about how great his tariffs have been for the United States, while promoting the myth that these policies will bring manufacturing back to the USA.

Meanwhile, Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, stood there like a submissive puppy, begging for scraps from the dinner table, and promised another $600 billion in investments in U.S. manufacturing—which, like the promises made in 2018, will probably never amount to much. This is especially likely since Apple does not have the capital to make such investments in the next five years, let alone the next twenty. Of course, it’s probably safer to assume that, under Modern Monetary Theory, stock buybacks are equated to domestic investment.

To see how absurd President Trump’s declarations and policies have been, perhaps a review of the dirty word rarely mentioned in economic discussions—”history”—is in order.

Smoot-Hawley Consequences

On June 13, 1930 the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act passed and almost immediately added the additional gasoline to the fire of the Great Depression worsening an already bad situation. President Hoover, a somewhat gentile yet arrogant man believing that his policies were always correct, ignored the letter from 1000 economists that by signing this act, international trade would collapse. Instead of opposing his own party’s fallacy into the teeth of a budding depression, President Hoover signed the act into law and the consequences were almost immediate.

The following data is from the Census Bureau’s historic pages as data collection during that era was sketchy at best and only beginning to come into its own as a viable science for measuring economic performance.

It does not take an expert to see the dramatic drop in average annual exports in 1931, after the Smoot-Hawley Act became the law of the land.

LBJ and Nixon Wage a Trade War

In the early years of President Kennedy’s administration, a new series of trade agreements with our allies was struck, nicknamed the Kennedy Accords, which provided a massive expansion in world trade where the physical volume of exported manufactured goods expanded by over 2.7 times between 1960 and 1970 (Source: Changing US Trade Patterns, by Jack L. Hervey, Economic Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago).

Unfortunately after his assassination, the Chicken Tax was imposed in January of 1964 and the first of many trade conflicts with the budding economic union in Europe began. Despite this minor trade conflict US exports continued at record levels until the mid to late 1960’s before it decline rapidly.

The approach to near balance in trade alarmed everyone in Washington, D.C., none more so than the man who would become President in 1971, Richard M. Nixon.

So why did Nixon elect to engage in a trade war shortly after coming into office?

The chart below explains the everything with data from 1967 through 1974 and the actions he took due to the stagnating US economy.

After years of a US trade surplus (NETEXP-US Net Exports) illustrated in red above, it crashed into a deficit in the early 1970’s as the US dollar held its value far above our European and Asian trading partners. So much so that President Nixon had to close the gold window in August of 1971, impose a 10% universal tariff on all manufactured goods, then devalue the US dollar in violation of the promises of the Bretton Woods Agreement.

In February 1973, market pressures lead to another devaluation of the dollar and an almost complete abandonment of the Bretton Woods Agreement sparking a boost in US net exports. It was not until the 1976 Smithsonian Accords that another attempt at a monetary agreement was implemented to re-stabilize the markets.

The Trump Trade Fallacy

President Trump’s bold economic and trade proclamations, where nations promise to invest in the United States and purchase our agricultural and manufactured goods, should be taken with a huge grain of exported salt (FYI, India is number one).

While nations make verbal commitments to purchase U.S. products, they are not foolish enough to engage in such purchases at a loss to their own domestic farmers and manufacturers. For example, Japan might purchase more rice from the U.S., but it will not be for domestic consumption. It is likely they will put some in storage and trans-export the remainder to another partner that will trade in yen.

Perhaps everyone believed the notion that Vietnam would purchase more U.S.-manufactured goods, but has anyone paid attention to the per capita income of the average Vietnamese citizen?

Obviously, Ford will not sell a lot of ready-to-be-recalled pickup trucks in Hanoi.

The truth is that the false promises made by other nations are a gambit—nothing more, nothing less. The idea for most of the countries involved in dramatic spending or importation announcements was to give President Trump the fake platitudes he desires, a photo op where he can announce, “See, I told you so,” to the world.

In reality, most intelligent foreign leaders just wanted to get the pictures over with, then engage in bureaucratic doublespeak behind the scenes for several years, waiting out Trump’s time in office to see if the next President might behave more rationally.

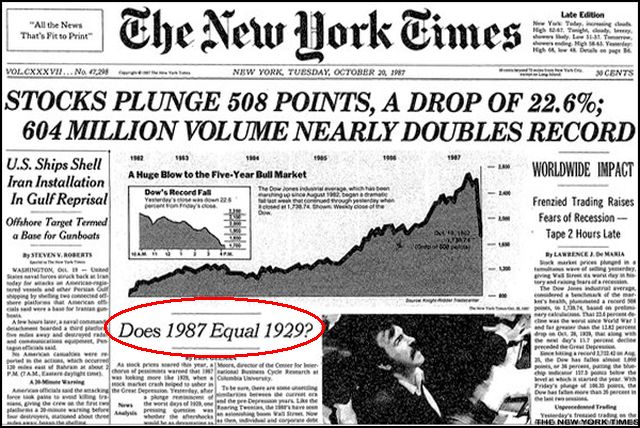

Unfortunately for the American public and American businesses, the results could dangerously deteriorate into a modern-day version of Smoot-Hawley all over again.

(title graphic courtesy of X’s @grok)